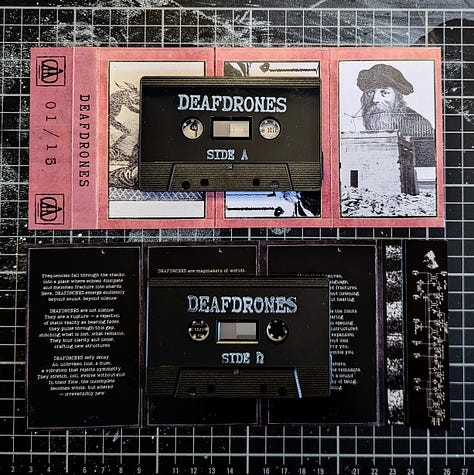

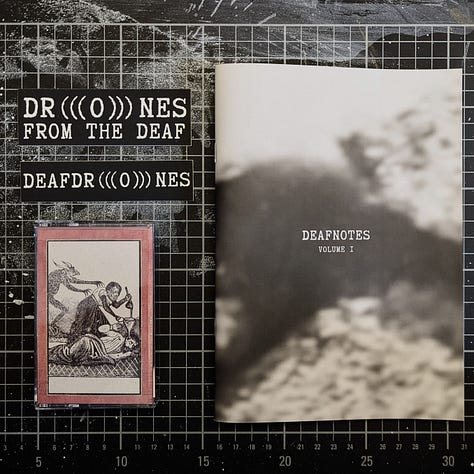

Sound has never been a stable continuum for me. It was always a ephemeral, fragmented phenomenon beyond my control. Without a doubt, my sensorineural hearing loss amplifies this instability - an acoustic world in flux, full of gaps, blurs and unreliable contours. It is this fragmentation of perception and my confrontation with its consequences that eventually led me to DEAFDRONES: a practice that explores sound as a pulsating field that cannot be captured in notation or classical structures. Drones offered me a way to question my own sonic reality - a reality that is never fixed, but always in the process of evolving and decaying.

But something was missing. Drones are like bridges to me. They carry and transform - whoever crosses the bridge is no longer the same as the person who once entered it. My focus was primarily on the process of crossing, the bridge as a medium with its own space. The completion of DEAFDRONES - and I really could have worked on it forever! - and with it the decision to complete the project, was the result of increasing pressure to find answers to questions that were increasingly preoccupying me.

More and more I began to ask myself what actually lies beyond these bridges, I was increasingly confronted with the idea of transcendence. The DEAFDRONES had shown me that sound is not just form or structure, but always also reciprocal effects and motion.

Particularly where I created endless loops with tapes in order to lose myself in a continuous drone, I discovered how fragile permanence actually is. Materials are finite, sensitive to interference - every action of even the smallest influence on the material had an effect on the further progression. Nothing sounded the same. At first I was annoyed because every recording had a different sound.

I gradually realized, however, that it was not about replicating for the sake of consumption, but about creating and maintaining an individual sound ecology. I realized that there are an infinite number of sound ecologies out there. Some are evident, others remain unheard. For example, noise pollution - the omnipresent, often overheard sound pollution - became the starting point of a new perception for me: every space is a sound ecology, whether we consciously hear it or not. But what happens when we not only document these ecologies, but transform them? When we understand them not as existing environments, but as shapeable territories?

For this reason, I am now launching my next project: X E N O V E R S E S - not as a counter-project to DEAFDRONES, but as its logical consequence.

XENOVERSES is my attempt to create unfamiliar sonic ecologies. Not replicas of pre-existing environments, but unique organic-artificial hybrids created through flawed, fragile materiality, technology and manipulation. I work with obsolete and revitalized sound carriers, with overlapping layers, with interferences.

XENOVERSES is not a mere sonic experiment - it is also an anthropological investigation of hearing itself. As Deaf Anthropologist, I move in an intermediate space: neither fully in the world of the hearing nor in that of silence. My hearing is fragmented, my perception unsteady. But it is precisely these fractures that shape my perspective. I don't hear like most people - but maybe that's why I hear differently.

In my own way, I want to show what happens when it is not about the perfectly perceived signal, but about the distortion, the absence, the hiatus. My approach is not an attempt to recreate the " natural " sound or to reconstruct lost frequencies. Instead, I ask: How do worlds sound that we only grasp in fragments? What other sound ecologies exist beyond standardized perception?

X E N O- (Greek ξένος, " alien", " foreign")

- V E R S E S (English universe, "cosmos, world")