As an audiovisual artist with profound sensorineural hearing loss in both ears, I hear the world differently. The limitations that come with my hearing loss could be seen as an obstacle, but I have learned over the years that they are also a source of inspiration and creativity. In my previous DEAFNOTES001 and DEAFNOTES002 I talked about my perception of noise, which can have its origin in external (noise pollution) or internal conditions (sub tinnitus) and how I also incorporate this conceptually in my work. I gain and develop essential materials for my works from the surroundings of these phenomena. This results in field recordings of various ambient noises and events or sonic imitations of tinnitus experiences, which I then mix as drone samples. However, this is only a small part of the repertoire that accompanies me in my work.

I have hearing aids in both ears that use technology to help me cope with everyday life, but they cannot fully compensate for my deficits. The reason for this is the type of hearing loss:

Sensorineural hearing loss, affects the inner ear, the auditory nerve or the brain centers responsible for hearing. Unlike other forms of hearing loss where sound is simply blocked or muffled, sensorineural hearing loss means that certain frequencies and sounds are either not heard or are distorted. In my case, this means that I often can't hear high frequencies and have difficulty classifying sounds spatially.

A healthy ear can localize sounds precisely in spatial terms, which is essential for orientation and understanding environments. However, this spatial hearing is very limited for me. For example, when I'm in a room full of people, the murmur of conversation blends into an indistinguishable carpet of sound from which I find it difficult to filter out individual voices. I also often find it difficult to locate sounds coming from behind or from the side.

Hearing aids are advanced electronic devices designed to help people with hearing loss improve their ability to communicate and hear the world around them. Actually, sensorineural hearing loss is the most common form of hearing loss and results from damage to the hair cells in the inner ear or the auditory nerve. As this damage is irreversible, hearing aids cannot cure hearing loss, but they can significantly improve hearing.

Sensorineural hearing loss is often characterized by the fact that certain frequency ranges of hearing are affected more than others. Modern hearing aids are therefore programmable and can be individually adjusted to the wearer's hearing profile. Audiologists use hearing tests to measure the specific hearing ability in different frequency ranges and calibrate the hearing aid accordingly. This allows amplification to take place exactly where it is needed most. However, it is important to understand that hearing aids cannot restore full hearing. They are aids that improve hearing, but they cannot completely replace natural hearing functions.

Without hearing aids, as a person with profound sensorineural hearing loss, I experience the world as almost completely mute. Everyday sounds such as conversations, traffic noise or music disappear, which can lead to a feeling of isolation. Communication becomes a challenge as lip-reading and gestures become the primary means of communication. The lack of acoustic feedback can create insecurity in social situations. In addition, the ability to spatially locate sounds is often lost, making it difficult to navigate the environment. Although this silent world can seem peaceful, it also increases the feeling of disconnection from hearing society and requires constant adaptation and creativity in everyday life.

These limitations have made me sharpen other senses and find alternative ways to interact with my acoustic environment. In my artistic work, I have learned to turn my disability into a source of strength. I have developed a range of techniques to gather the information I am missing due to my hearing loss. In the process, the body has become an important resonance instrument through which I perceive sounds in a new way.

As I cannot hear many sounds in the usual way, I concentrate on the vibrations and oscillations they produce. By touching and feeling surfaces, I can perceive the intensity and texture of sounds. I use special devices that convert sound into vibration and wear headphones that transmit vibrations directly to my body. In this way, I experience music not just as sound, but as a multi-sensory experience.

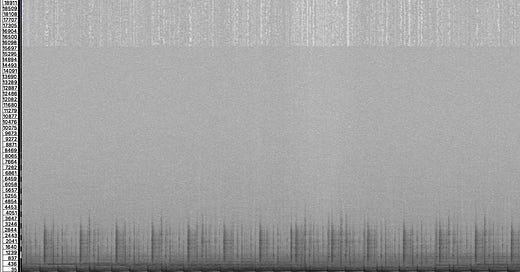

To better understand sounds, I use visual representations such as spectrograms that convert frequencies into graphics. These visual tools allow me to analyze the structure of sounds and recognize patterns. By seeing what I cannot hear, I have learned to understand sounds on a deeper level. This has helped me to further develop my sound design skills and add new dimensions to my audiovisual works. I see my work as an invitation to explore the world of sound in new and unexpected ways.

Without the ability to hear sounds completely and precisely, I have learned to pay attention to other aspects of sounds. The textures, the emotions and the stories that sounds convey are at the center of my work. I create soundscapes that are not only based on what I hear, but also on what I feel and see.

As I often reach my limits on my own, I like to collaborate with other artists and technicians who help me to realize my visions. These collaborations open up new perspectives and allow me to enrich my projects with a variety of impressions and ideas. This exchange often results in new creative approaches and innovative solutions to technical challenges.

My sensorineural hearing loss has taught me to look at the world of sound from a different perspective. It has forced me to be creative, to find new ways and to focus on what really matters: the essence of sound. In my work as an audiovisual artist, I don't see my hearing loss as a weakness, but as a valuable source of inspiration and innovation.

In a world where the visual often dominates, engaging with the aural dimension offers a refreshing perspective and reminds us that art can and should engage all the senses. Whether listening or feeling, sound is always there, ready for us to explore. Or in the words of the poet John Keats (1795-1821):

'Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter'.