“The world is intrinsically silent.”

These words from Michel Faber’s Listen have left a lasting impression on me — so much so that I haven’t been able to continue reading. A sentence that struck me like a line from a Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, something formulated with such sober clarity that one instinctively thinks,

“Y e s , of course, that’s true.”

Yet, its full meaning remains elusive, difficult to grasp or articulate. For some time now, I’ve been asking myself: what does it mean for the world to be fundamentally silent?

What is left when every sound, every melody, every acoustic experience is nothing more than an interpretation through our hearing—and what happens when that very hearing becomes fragile, unreliable, or broken?

For me, this question is more than a thought experiment. It delves deep into a reality I face daily: a hearing that refuses to map the world in clear melodies and harmonious structures. Instead, I perceive the world through a mesh of noise, distortions, and gaps. It’s as if — whether with or without hearing aids—I’m listening through a filter that unpredictably decides what reaches me and what doesn’t. I often compare my hearing to a damaged radio broadcast — one where the signal constantly cuts out, where static fills the space until a moment of clarity breaks through.

A Changed Relationship with Sound

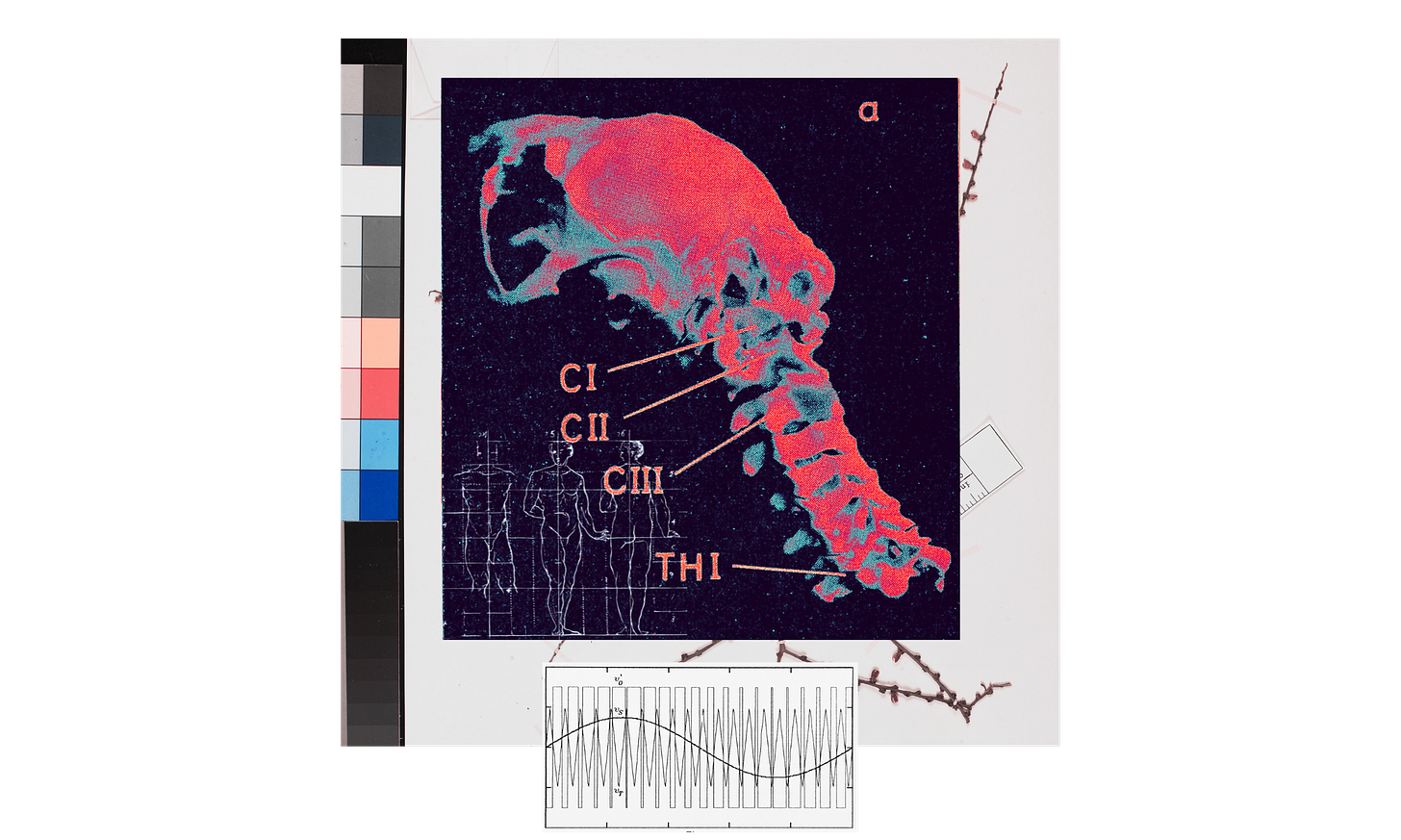

The notion that the world is “intrinsically silent” resonates deeply with my experience. Absolute silence, in the natural world, doesn’t exist — at least not in the romantic sense we often imagine. Sound waves are all around us, constantly generated by movement, wind, voices, machines. They are a physical reality — they exist whether we can hear them or not. But the way they are transformed into sound is profoundly subjective, shaped by the biological and psychological filters each individual carries.

In my case, with my hearing gradually losing its sensitivity since childhood, the subjective nature of sound has become starkly evident. My inner ear is, in a sense, “an instrument that has lost its tuning.”

Sounds that were once clear and distinct now reach me with distortion. The high-pitched beep of a smoke alarm now resembles the distant hum of an insect — and the paradox is: I can no longer perceive the actual hum of a distant insect. Where others might be driven mad by the chirping of crickets, I hear n o t h i n g at all. The frequencies shift, harmonies break apart, and I often find myself lost in a labyrinth of dissonances, where a clear melody is hard to grasp.

To others, this might sound like a torment, and yes, there are days when the cacophony of my own perception wears me down. But there is also another side. I have learned to accept the distortions and irregularities as part of my own acoustic reality. It’s as if I live in a world where the lines between sound and noise blur, where order and chaos are no longer clearly distinguishable. Noise and dissonance are not alien concepts to me, but familiar companions that have opened up a new dimension of sonic perception.

The Evolutionary Value of Hearing: Survival and Aesthetics

Humans have evolved over millennia to navigate a world full of sounds and acoustic signals. Our ancestors needed the ability to interpret the rustling in the underbrush to detect an approaching predator or prey. Animals continue to do this with incredible precision: bats navigate in darkness through ultrasound, dogs hear frequencies long beyond our range, and birds communicate through subtle nuances over great distances.

This ability to interpret acoustic signals is a matter of survival. It helps us recognize dangers and find our way in the world. I, too, have this ability, but my threshold for what counts as a “warning sound” has shifted. I can’t hear the gentle patter of rain, but I can feel it. The low rumble of thunder reaches me as a distant vibration, resonating through my body—more felt than heard. It’s an acoustic reality that relies more on the physical, on sensing vibrations and resonances.

Yet humans are more than survivalists — we are also aesthetic beings. « A N I M A L _ A E S T H E T I C U M » We don’t just seek out patterns in the sounds around us to identify threats; we strive for beauty in music, in harmony, in the arrangement of tones. Why else would we have invented music, if not for the sheer joy it brings us?

For me, with my compromised hearing, music is more than a source of aesthetic pleasure. It’s a means of processing the silence and the noise within me. When I returned to making music under the name Deaf Anthropologist, it wasn’t a return to what I had known before, but rather an exploration of what I can hear now — and what I can no longer hear.

I work with drones and noise, with static soundscapes that shift gradually, transforming like a river flowing endlessly from one form to another. For me, this isn’t a rejection of order, but an attempt to find a new kind of structure in my sonic world — a structure defined not by harmony, but by resonance.

Finding Beauty in Noise

For many, noise and dissonance are irritating, even unpleasant. They are sounds that refuse to fit into a harmonious system, that don’t follow the familiar patterns that so often give us a sense of security. Yet it’s precisely these sonic irregularities that fascinate me. Perhaps because I see myself in them—in the breakage, in the unpredictability, in the refusal to conform.

It’s paradoxical that despite my limited hearing ability, I seek out aesthetics in noise, beauty in chaos. But maybe it’s because I don’t perceive dissonance as merely disruptive; I see it as a gateway to a deeper, more fundamental truth about sound. That truth is this: sound is always a form of interpretation.

There is no such thing as “pure hearing,” no listening that is free of biases and expectations. Every frequency I perceive is the result of an interplay between what reaches me from the outside and how my hearing and brain process it. When I listen to noise, I am also listening to the limits of my own perceptual apparatus.

The Space Between Sound and Silence

When I performed SPACES & GRAVITY, this tension between sound and silence, between order and chaos, found tangible form. The dome of the Oskar Lühning Telescope, where I performed alongside my wife, has a unique acoustic quality — a long reverberation that stretches sound. Every tone I played was absorbed, altered, transformed by the space — it was as if the architecture itself had found a voice.

In those moments, I didn’t feel like a musician generating sound, but rather as someone letting sound flow through the space, shaping it but not controlling it. The world may be intrinsically silent, but it holds endless potential for sound — if we are willing to engage with it, with the noise and dissonance, with the fleeting moments of clarity that shimmer through it all.

Sound as a Mirror of Our Limitations

“The world is playing us”

In the end, my hearing, my music-making, my entire experience of sound is a dialogue with the limits of my own body. My hearing may be damaged, but that doesn’t mean I’ve stopped listening — it just means I listen differently. And this “different listening” allows me to shape sound in ways I would never have discovered otherwise.

Perhaps that’s what I appreciate most about noise and experimental music: they reveal how limited our understanding of sound truly is. They push us to leave familiar pathways and dive into new sonic worlds. And they remind us that silence and sound are not opposites, but rather mutually dependent—two sides of the same coin.

In silence, I find not just the absence of noise, but a kind of acoustic shadow space, where the echoes of past sounds mingle with the distortions and noise of my present perception. This way of listening—not quite tangible, not fully nameable—has become a means for me to shape my own, subjective sonic world. And it is here that I encounter a paradoxical feeling: even though the loss of much of my hearing has cast me into a kind of acoustic isolation, I have also developed a new, intimate relationship with the sounds I can still perceive.

My drones and experimental sounds are not only an expression of an aesthetic pursuit; they are also a way of engaging with my own hearing perception. They are an attempt to make audible the space between what I could hear and what I actually hear. It’s a play with the uncertainties and fractures in my perception — a constant negotiation between

clarity and blur,

sound and silence.

And perhaps that’s where the deeper connection to Michel Faber’s idea of the “intrinsic silence of the world” lies. Because if the world is fundamentally silent, then it is up to us to give it a voice, to interpret it, and to let it sound in our own way. This applies to humans as much as it does to animals that navigate through sound — but while for animals, sound is often directly tied to survival, for us, it opens a door to an aesthetic and emotional world that defies simple categorization.

For me, this world is not less rich just because my hearing is incomplete. On the contrary — it’s an invitation to see the limitations as an opportunity to create new sonic realities. Every piece I compose, every moment I navigate through noise and dissonance, is an act of empowerment.

A dialogue with a world that is silent yet has so much to say.