The year 2024 ended with a peculiar acoustic experience on Christmas Eve. I had retreated some 800 kilometers away, into the southern reaches of the Black Forest. I found myself sitting, heavy with thought, at a table in a cozy, warm lodge. Before me were a cup of tea and a few leftover Christmas cookies, which I had yet to touch. My notebook lay open, capturing fragmented pieces of an idea that flitted about my mind, still in its embryonic stages.

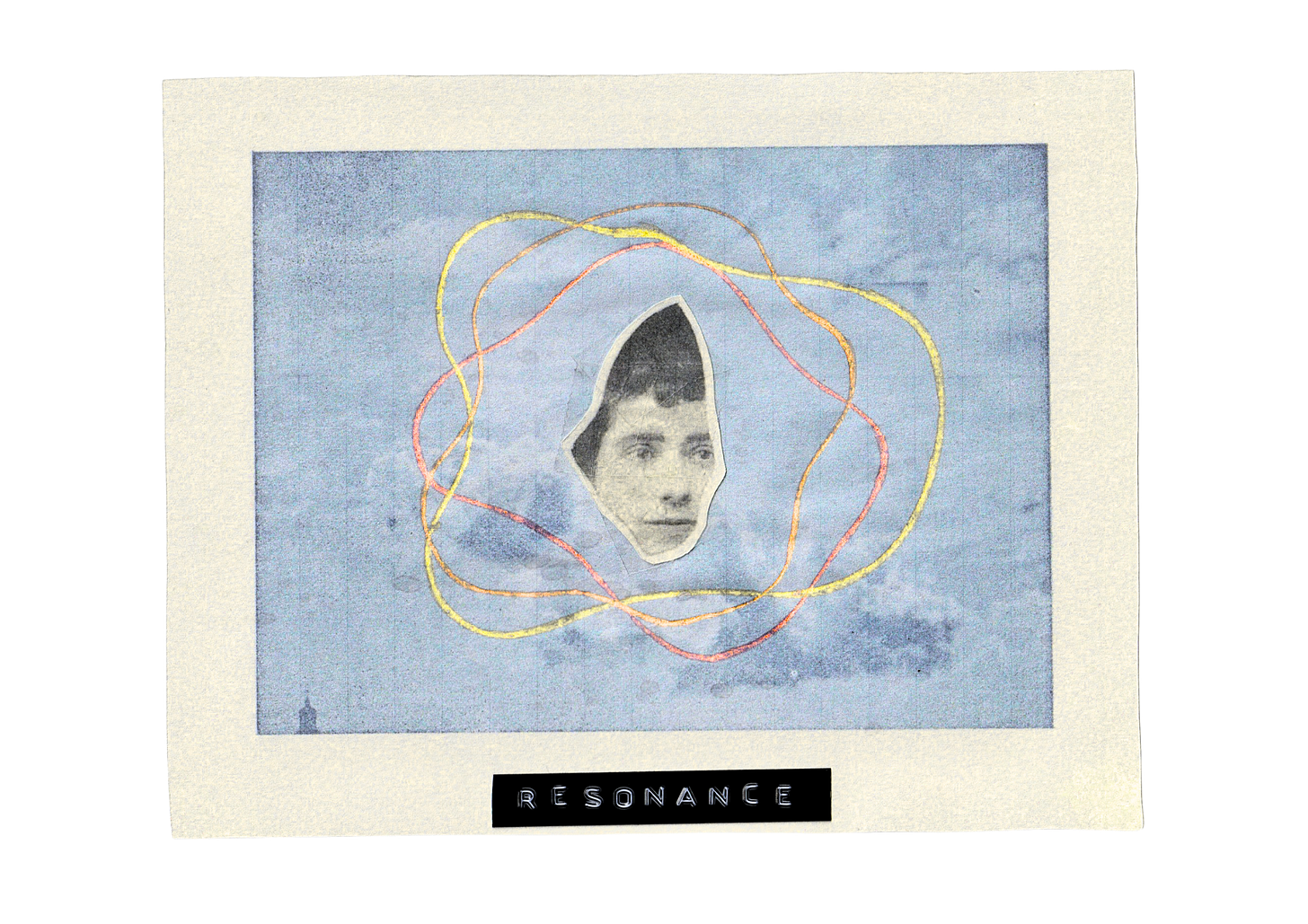

After a relentlessly busy summer, much of my time had been spent reflecting on the evolution of the DEAFDRONES format. As it stands now, I would describe

DEAFDRONES as a collage of sonic experiments — a dialogue with my own hearing impairment, my subjective perception of sound and space, and intersecting themes like noise pollution and environmental sound design.

It is part of my self-initiated, independent artistic research as Deaf Anthropologist.

I gather all manner of materials: audio and video recordings, photographs, text — virtually anything that crosses my path — and integrate them into DEAFDRONES in various ways. To maintain focus amidst the volume of material, I’ve learned that periodically sitting down with a notebook helps. In those moments, I record progress and setbacks, map connections between themes, or rearrange and distill elements into clarity.

As I sipped on what had become a cold herbal tea, I realized I had stopped writing altogether. I wasn’t even actively thinking anymore; I was simply sitting there, rooted to the spot, listening intently to an expansive, floating sound that slowly enveloped the room like a cascading fabric. It hypnotized my senses, yet instead of inducing lethargy, it sharpened my attention. I found myself captivated rather than subdued.

What was this sound that held me so completely?

I wanted to uncover its source, but as so often happens, my directional hearing betrayed me. Locating and identifying sounds has always been a challenge, leaving me unsure where to even begin my search. I resorted to my usual process of elimination — acoustic phenomena often unsettle me, thanks to my impairment, and deciphering them is a daily exercise in patience.

This wasn’t tinnitus; the frequency was wrong, too high. Still, I tested the hypothesis. I switched off my hearing aids and set them aside. Nothing. Were it tinnitus, I would still have perceived it. I put my hearing aids back on, and as they powered up, there it was again. The search continued:

the fridge?

Its hum could be quite loud at times. I leaned my head against its cold, lacquered surface.

No.

The dryer? A neighbor?

All dead ends.

For me, ambiguous sounds often leave room for interpretation; their identity emerges only gradually, piece by piece. I wandered through the lodge, pressing my ears against walls and appliances, feeling increasingly absurd as I tried to pinpoint the source of this unrelenting, low, evenly pulsating tone. I began to doubt my sanity —

how long had I been hearing this? Was it still there, or was I now only hearing an echo in my mind?

Being alone didn’t help. Were someone with sharper hearing present, they might have identified it in an instant:

“Oh, that’s just XYZ.”

Mystery solved.

Instead, I focused my senses and adjusted my hearing aids to their maximum setting. Now, every noise risked jolting me from my skin — should a door slam or someone unexpectedly speak to me, the piercing, hyperamplified metallic sound would startle me to the core.

But the sound persisted, this time revealing a subtle structure, almost a melody.

Was this real, or an auditory pareidolia?

Pareidolia — a phenomenon where the mind perceives familiar patterns in randomness — is often associated with visuals: faces in clouds, figures in rock formations.

In sound, this takes the form of auditory pareidolia, or as British artist and author Joe Banks terms it, Rorschach Audio. Our brains excel at pattern recognition, constructing coherence from incomplete or ambiguous stimuli. This sound, I realized, was provoking just such an illusion in me — a projection of structure onto the undefined.

I turned to the window and wondered, “Could it be coming from outside?”

When I opened it, icy wind rushed in, carrying the sound into my hearing aids’ hyperamplified microphones. The initial volume overwhelmed me, and I quickly adjusted the settings back to normal. Slowly, it dawned on me: these were the tolling bells of a cathedral in the quaint medieval town nestled at the foot of the hill.

I grabbed my phone and recorded about ninety seconds of this phenomenon using a simple recorder app. I felt like a ghost hunter capturing a specter, a fleeting encounter with something ethereal. Here it was — this brief recording of the sacred on Christmas Eve, unnoticed by anyone else in the town, I imagined.

Only weeks later, in the new year, did I revisit the recording. It captivated me so profoundly that I decided to base an entire project around it. Exclusively. By that, I mean using this single sample as both the foundation and the sole building block for a composition. In a way, this approach drew inspiration from Giacinto Scelsi’s “One Note Method”.

Scelsi’s radical approach shifts focus from melody and harmony to the deep exploration of a single tone. Born of his spiritual philosophy, his method treats a tone as a living microcosm, filled with infinite layers and variations. Through techniques like microtonal shifts, dynamic fluctuations, and timbral changes, Scelsi uncovered the depth within simplicity. To him, music was a meditative journey, where sound itself became the medium of universal energy. Inspired by his minimalist ethos, I sought to apply this principle to my sample.

Digital and analog tools offered ample possibilities for transforming the recording. Techniques like spectral analysis and resynthesis allowed me to isolate and reimagine overtones and textures, using tools like Max/MSP, SPEAR, and Ableton’s Spectral Resonator. Granular synthesis fragmented the sample into tiny grains, rearranged to create dynamic soundscapes. Extreme time-stretching and pitch-shifting unearthed hidden details, while feedback loops organically evolved the sound. These techniques enabled me to turn something as ordinary as a church bell into a hypnotic, sacred auditory phenomenon.

In the end, I limited myself to three tracks to maintain focus. Each worked with the same sample but applied distinct techniques: one stretched the sound with reverb, another isolated specific elements, and the third manipulated grains across a spectrogram. Through this quite minimalist approach, I aimed to capture the hypnotic essence of the original experience.

This encounter was more than a random brush with sound — it reaffirmed the core of my artistic practice. That Christmas Eve chime became a symbol of the potent

ial within subjective perception, particularly one shaped by hearing loss. In that seemingly simple sound, I discovered a new perspective (again), deepening my relationship with space, time, and sound itself.

As 2024 drew to a close, I came to a further understanding: my work as Deaf Anthropologist thrives on exploring the hidden and uncertain within sound. My hearing impairment compels me to experience sound in fragmented yet radically focused ways. This limitation, paradoxically, enables transformations that might otherwise remain unattainable.

Art, I’ve realized, isn’t just about crafting the obvious. It’s about rendering the invisible and inaudible tangible. It’s an invitation to notice the unremarkable, to give it space and weight. Often, it’s within the quiet, overlooked moments of everyday life that the greatest potential for transformation lies.