In the hustle and bustle of our modern lives, there's hardly anything that accompanies us as relentlessly as the noise of civilization. Whether it’s the roar of traffic, the hum of air conditioners, or the metallic clatter of construction sites—these sounds are so ingrained in our daily existence that we often perceive them as mere background noise, something mildly annoying yet ever-present. Since the 1960s, we’ve even had a term for this phenomenon: noise pollution. This concept emerged alongside a growing awareness of environmental issues, among which the impact of urban noise became increasingly recognized.1

In one of my previous DEAFNOTES, I mentioned how this awareness and engagement with noise pollution arose during the COVID-19 pandemic in connection with my own hearing impairment, and how I have since increasingly reflected this in my work. In the course of my artistic research on noise pollution — the contrast between silence and noise and everything that lies between and beyond — I came across the following quote:

"In the nineteenth century, with the invention of the machine, Noise was born. Today, Noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibility of men. For many centuries life went by in silence, or at most in muted tones."

This passage comes from the pen of the Italian painter and composer Luigi Russolo, written in the early 20th century. Russolo not only heard the noise of civilization; he transformed it into a new form of music — a music that still challenges and fascinates us today. Yet, as I delved deeper into his ideas, I became increasingly aware that Russolo's work also has a darker side, one that is deeply intertwined with the aesthetic and political currents of his time. What follows is a critical essay on aesthetics and responsibility.

Luigi Russolo, born in 1885 in Portogruaro, Italy, began his artistic career primarily as a painter, blending the movement of Symbolism2 with the technique of Divisionism3. Russolo joined the Futurist movement, founded by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909. The Futurists sought to radically renew art by rejecting the aesthetics of the 19th century, instead celebrating the speed, technology, and violence of modern life.

Interlude: Marinetti & the ideological landscape of italian Futurism

The "Manifesto del Futurismo" by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, published on February 20, 1909, in the French newspaper Le Figaro, is considered the foundational text of the Futurist movement. It contains several passages that express these ideas.

"We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car, its body adorned with great pipes, like serpents with explosive breath... a roaring car that seems to run on shrapnel, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace."4

What begins here as the poetic fever dream of a visionary takes a dark, misogynistic turn in another section of the manifesto that sends a chill down my spine.

"We want to glorify war—the world's only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gestures of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman."

Indeed, many of the Futurists, including Marinetti, actively fought on the front lines of World War I. However, the confrontation with the harsh reality of the war led to a disillusionment among some of them. The initial glorification of war and violence as a means to renew society was challenged by the brutal reality of the conflict. The destruction, once idealized as the "hygiene of the world" revealed itself as a devastating force that not only tore down old structures but also caused unimaginable human suffering.

After the war, Marinetti continued to support fascism, which rose to power in Italy in the 1920s. He saw in Benito Mussolini and the fascists the force that could implement the radical changes the Futurists had envisioned. Marinetti and other Futurists perceived fascism as a movement that captured the dynamism and revolutionary impulses of Futurism and translated them into political action. This led to a closer intertwining of Futurism and fascism. Marinetti supported fascist militarism, which emphasized strength, discipline, and authoritarian control because he believed it provided the necessary foundation for building a new, modern society. Yet, while he supported militarism, his original glorification of war as an entirely positive phenomenon was no longer present in the same form. In his view, war became more of a means to strengthen the fascist state and achieve its goals, rather than an end in itself or a celebrated ideal.

Marinetti continued to endorse fascist militarism and violence because he saw them as necessary tools for implementing fascist ideals and achieving a new social order. However, his initial romantic and enthusiastic glorification of war gave way to a more pragmatic view, in which war, though still seen as necessary, was no longer celebrated as the highest ideal.

The discovery of noise

But let’s return to Russolo, before the upheaval of World War I. Amid these contradictory and revolutionary aspirations, Russolo developed a particular fascination with sound, especially the noises of industrial civilization. The question arises: why? Why would Russolo, formerly a painter, now turn his focus to the study of sounds?

On one hand, it was undoubtedly a desire for innovation. Russolo was driven by the wish to push the boundaries of traditional art forms. He saw painting as a medium no longer capable of adequately expressing the new reality shaped by machines and technology. To capture and convey the urban and industrial noise of the modern world, Russolo turned to sound. His vision was to create a new art form that could encapsulate the "noise" of the modern world in a way that resonated with the intense energy and dynamism of Futurist ideals.

On the other hand, Russolo’s interest in sound can also be seen as a natural evolution of his artistic practice. As a painter, he had already engaged with Divisionism, a technique based on the perception of light and color. The shift to sound art could be viewed as an extension of this interest in perception and sensory experience. For Russolo, sound represented a new dimension of perception, allowing him to explore the chaotic and dynamic qualities of the modern world artistically.

This fascination with sound led Russolo, in 1913, to write his manifesto "L’arte dei rumori" ("The Art of Noises"), which in many ways laid the foundation for modern experimental music.

In "L’arte dei rumori," Russolo writes:

Ancient life was all silence. In the nineteenth century, with the invention of the machine, Noise was born. Today, Noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibility of men. For many centuries life went by in silence, or at most in muted tones. The strongest noises which interrupted this silence were not intense or prolonged or varied. If we overlook such exceptional movements as earthquakes, hurricanes, storms, avalanches and waterfalls, nature is silent.

With this observation, Russolo begins his plea for a new kind of music, one that embraces the sounds of modern life. He argues that the industrial revolution has not only changed our cities and workplaces but also the “silent” soundscapes that surround us. Traditional harmonies of classical music, he contends, are no longer capable of expressing this new reality. Instead, music must incorporate the sounds of machines, factories, and cities to create the "soundtrack" of modern life.

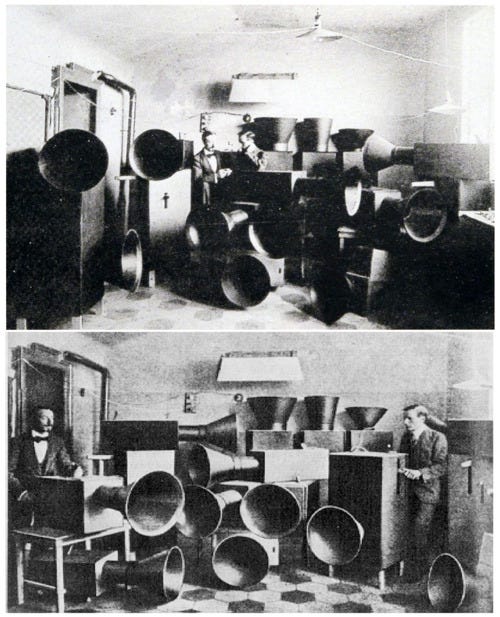

These ideas led Russolo to invent the Intonarumori, mechanical instruments capable of producing a wide range of noises—from deep rumbles to sharp screeches and complex rhythmic patterns. These instruments, which often look like grotesque machines, became for Russolo the tools to create a new kind of music. His "music of noises" was loud, dissonant, and often disturbing, but it had a clarity and power that forced listeners to hear the world around them with new ears.

Luigi Russolo was not only active as a theorist and composer, but he also presented his "Music of Noise" to a broader audience through live performances. These performances often took place within avant-garde circles, including silent film theaters, where his "Intonarumori" instruments radically disrupted conventional musical experiences. The reactions to these performances were often intense and sometimes chaotic. Reports suggest that on several occasions, these events escalated into full-blown riots, as the audience, shocked and angered by the dissonant and mechanical sounds, resorted to revolts and acts of violence. Accustomed to the harmonious accompaniment of piano or orchestra, many found Russolo’s noise music to be an unbearable provocation.5

A well-known example of such escalation occurred during a performance in Milan on June 2, 1914, at the Teatro Dal Verme. This concert was one of the first occasions where the public experienced his experimental compositions live. Russolo, together with his colleagues, performed before an audience that largely consisted of Futurist supporters but also included curious spectators who were less familiar with this avant-garde art form. What began as an artistic experiment ended in a full-fledged scandal: many in the audience reacted with loud protests, threw objects at the stage, and engaged in brawls that ultimately had to be quelled by the police. These incidents highlight the polarizing nature of Russolo's work and demonstrate how his "Music of Noise" brought not only aesthetic but also social and emotional tensions to the surface. This underscores the radical power of his art, which challenged existing artistic norms and confronted the sensibilities of a rapidly changing society.

Conclusion

Yet, as much as Russolo’s creative and aesthetic ideas fascinate me, I am also aware that his works cannot be separated from the political and social developments of his time. Futurism, of which Russolo was a part, was not just an artistic movement but was also deeply entangled with the ideology of fascism. I often find myself questioning whether Russolo’s "music of noises" was more than just an aesthetic innovation—whether it also represented a problematic glorification of industrial violence and authoritarian control.

One central point that should give us pause is Russolo’s enthusiasm for noise as an expression of the modern world. While he viewed noise as artistic material, we could also see this as a metaphorical embrace of the chaos and violence that accompanied the technological and industrial revolution. This revolution brought not only progress but also immense suffering — an aspect that is often overlooked in the celebration of modernity.

But perhaps Russolo himself was not fully aware of the ambivalence of his work. In creating the Intonarumori, he may have seen himself as a kind of prophet of the future, one who could harness the forces of noise and chaos to create something new and beautiful. Yet, in doing so, he also opened a door to an aestheticization of violence, a door through which fascism would later walk with its militaristic and authoritarian ideas.

Of course, it would be simplistic to dismiss Russolo entirely because of these connections. His work has influenced countless artists and musicians and opened up new possibilities in the exploration of sound. But it’s equally important to recognize the complexities and contradictions inherent in his work. We cannot view his achievements in isolation from the historical and political context in which they arose. Instead, we must engage critically with his ideas, considering not only their aesthetic innovations but also the darker aspects they might reveal.

In this sense, Russolo’s Intonarumori are both a celebration and a critique of modernity. They reflect the excitement and energy of a world in transformation but also point to the potential dangers of an uncritical embrace of technology and industrialization. For me, this tension between innovation and responsibility is central to understanding Russolo’s work — and it’s a tension that remains relevant in our own time, as we continue to navigate the complex relationship between art, technology, and society.

Ultimately, Russolo’s work challenges us to listen more closely to the world around us. It encourages us to embrace the unfamiliar and the dissonant, to find beauty in what at first seems chaotic or disturbing. But it also reminds us of the responsibility that comes with this exploration — to remain aware of the broader implications of our work, and to consider not only what we create but also the context in which it exists.

In reflecting on Russolo’s legacy, I find myself returning to his Intonarumori with a mixture of admiration and unease. They are a testament to the power of art to transform the everyday into something extraordinary, but they also serve as a reminder of the need for critical reflection. In celebrating the sounds of modern life, we must also be mindful of the noise we contribute to the world — and consider how we might find harmony in the cacophony.

A significant milestone in this awareness was the publication of *"The Noise Pollution Problem: Background, Criteria, and Control"* by S. Newman and W. Berglund in 1970. This book was one of the first comprehensive studies on noise pollution, helping to popularize the term further. In the 1970s, governments and environmental organizations began to take the issue more seriously, leading to the development of laws and guidelines aimed at protecting people from noise-related disturbances.

Symbolism was an art movement that developed in the late 19th century, aiming to go beyond realistic representation to convey emotional, spiritual, or mystical content. Symbolist works were often characterized by mystical, dreamlike, and allegorical themes. In Russolo’s early works, this symbolist tendency is evident as he sought to depict the invisible and the supernatural in his art.

Divisionism, developed by artists like Georges Seurat and Giovanni Segantini, involved the use of small dots or strokes of pure color, which would blend optically when viewed from a distance. This technique aimed to achieve more intense color effects and was adapted by many Italian painters of the time.

Samothrace, a Greek island in the northern Aegean, is best known for its significant archaeological site, the Sanctuary of the Great Gods. In antiquity, this sanctuary was a major center of religious practices and mystery cults, renowned throughout the Greek world. The island was a place where people sought spiritual renewal and performed enigmatic rituals to gain protection and prosperity. However, the most famous discovery on Samothrace is the Nike of Samothrace, an impressive marble statue of the winged goddess of victory, now displayed in the Louvre in Paris. Created around 190 BC, this statue is a masterpiece of Hellenistic art and symbolizes triumph and divine favor.

Michael Kirby and Victoria Nes Kirby's book "Futurist Performance," which provides a detailed examination of Futurist performance art and its often controversial reactions. Further insights can also be found in R. W. Witt's works, such as "The Futurist Noise Machines of Luigi Russolo," as well as in specific monographs on Luigi Russolo and the Futurists.